Management Grounded on Principles of Flow

I was reading Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience again over the weekend (highly recommended if you haven't read it). Flow is one of the most important recent academic work in psychology that captures the universal state and motivation for human happiness. It’s that feeling you get when you’re “in the zone”: fully in control while performing an activity with clear goals and immediate feedback; where the rest of the world fades away, allowing you to achieve higher levels of performance in a new focused state of consciousness. I’m iterating on this idea: a management framework for fostering happiness, productivity, and individual growth, grounded on the principles of flow.

I first read Flow years ago, shortly after joining the Concept Lab, in an "individual contributor" capacity attempting to design engaging experiences for customers - to help them get in the flow of recreational shopping (I think it was a backwards progression from The Paradox of Choice to Thinking Fast and Slow to Flow). The primary reason I read it this time was because I’ve been in search and refinement of my ikigai since the start of this year - my new year’s resolution for finding sustained happiness - and have also been experimenting with purposeful flow state induction for some time. Reading it now through the lens of a people manager, I noticed the condition for flow makes for a great set of management principles. It requires active nurturing from management and leadership team, but if harnessed properly and redirected towards work-related tasks and activities, it could increase focus, agility, impact, and overall happiness within the team.

This is super early thinking so I’m really open to feedback. It involves three components for management team to focus on in order to nurture flow: (1) the team – creating the conditions for flow at the team level through clear goals, tasks, and decision-making; (2) the individuals – identifying unique flow state conditions for each team member; and (3) the culture – fostering an environment for sustained happiness. This is partly inspired by a conversation I had with a colleague last week where he shared his key components around management success which includes (1) the product – being concise about what the team works on, (2) the people – focusing on measurable individual growth, and (3) the team culture – creating a supportive environment and unique identity within the team. Note: this framework is dependent on the notion that purposeful flow state induction is possible not just for everyone but also for a range of assigned tasks. I’m aware that psychological entropy affects individuals differently which impacts their ability to enter a heightened state of focus, and that not all types of activities are enjoyable by everyone. However, reading, writing, and engaging is social environments are activities where people can often enter flow state. This should extend to other creative and functional skills we use in a work setting. My predisposition is that flow state is always possible as long as we control the optimal conditions which requires removing/minimizing possible detractors.

The Team

Flow starts from clear expectations at the team level, which helps build clarity and motivation around the work. Below is a list of conditions and effects that people describe when experiencing flow state (note: not all have to be true to achieve this state).

- task that can be completed

- requires concentration

- focused on clear goals

- immediate feedback

- deep and effortless involvement, removed from awareness of daily life

- control over actions

- stronger sense of self after flow state

- duration of time is altered

It seems possible to control the first four conditions at the team level through the team's operational model. This is fairly standard at Amazon: a document that describes the team’s mission and decision-making. It generally covers the vision for the team, the overarching goals, the current priorities that contribute to those goals, how reviews are conducted (mechanisms for feedback); all of which help individuals on the team understand their tasks better and how it contributes to the team’s success. It helps team members calibrate with what they should be doing and how their work contribute to the overall business. One of my previous managers, coming out of an executive leadership training, had created a personal operational model document and encouraged his leadership team to do the same. This was helpful to capture things that didn’t belong at the team operational model – like his availability, what he needs to be informed on, and what situations require him to be a decision-maker/breaker. This team and leadership operational strategy is best communicated at the team level and has the effect of turning potentially bleak objective conditions into subjectively controllable experiences by creating clear decision-making guidelines that can help individuals stay focused (reduced chance of straying out of the flow channel, more below).

The Individuals

Beyond the team level, nurturing flow requires managerial calibration with each individual on the team. The difficulty is that each of us is temperamentally sensitive to a certain range of information that we learn to value more than other people. Assuming the goals / team objectives are fixed, then calibration should be focused on individual motivation (what drives them) and scope (what they're expected to deliver). Success here requires understanding of both functional skills and offering appropriate work challenges to keep employees in the flow channel.

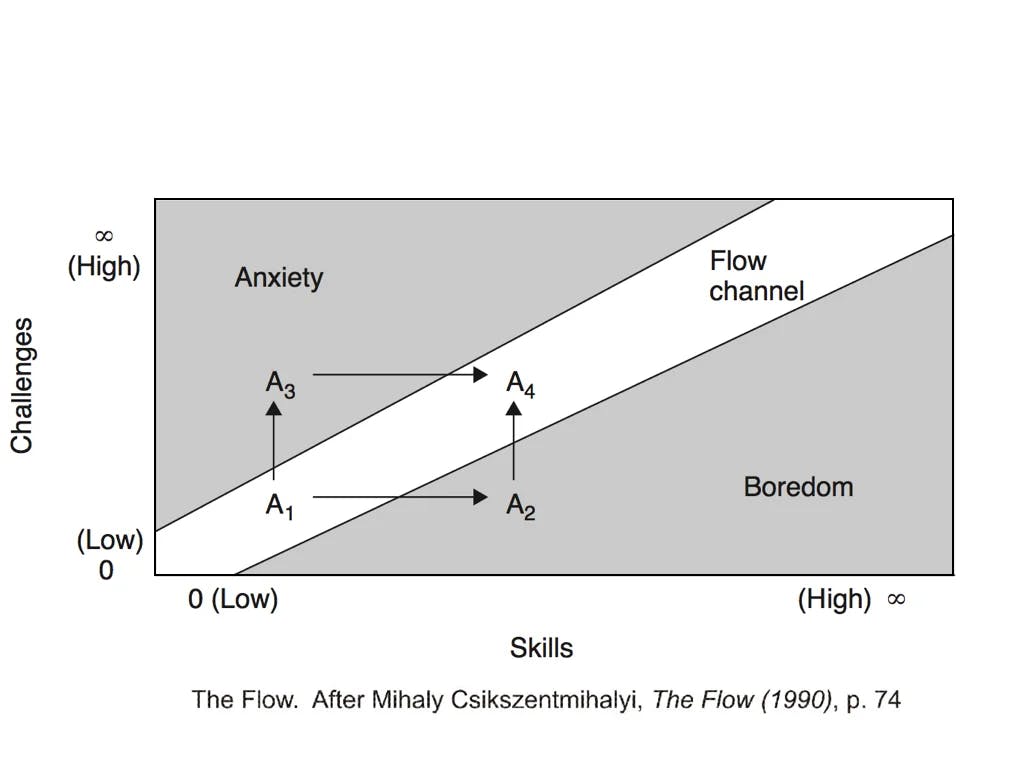

The Flow channel is a state in which the task or activity performed aligns with the team goals and is challenging but achievable, which in turn leads to continuous growth. It’s possible to develop skills to take on more challenging problems that are either bigger in scope or difficult in complexity (moving from A₁ to A₄). There’s a danger in pushing the individual too hard which could induce high anxiety (A₃) or putting the individual on problems that aren’t challenging enough (A₂) which could lead to boredom; both have the consequence of breaking them out of the flow channel. This maps somewhat to the adaptive learning model: when picking up a new skill (especially something with a high skill floor), it’s easy to be overwhelmed by the challenge. This is called going against the grain, and can result in a total abandonment of the learning objective. The success at this stage requires that managers are attuned to individual team members, provide a challenging scope of work, and create a safety net so that everyone feels comfortable taking risks.

The Culture

I’m still fleshing this section out, but the central point I want to capture here isn’t necessarily just creating team culture within the work environment but creating a culture that encourages and supports sustainable happiness which may occur outside the work environment and is potentially unrelated to work. It could be active, like helping individuals form atomic habits, but I believe sustainable happiness comes more from one’s ikigai.

Ikigai is the Japanese concept of finding joy and living a fulfilling life; a person’s reason for living. As a personal anecdote, my journey began at the start of the new year, as it often does for people looking for a reset, resolution, or a radical improvement. I was feeling less fulfilled at work; at home, our newborn was constantly keeping us up through the night which added to the stress. It took a lot of introspection and experimentation, but I realized that the thing that brings me purpose - my ikigai - is constantly learning new things (especially across different domains) and finding opportunities for practical application. I now wake up around 5AM every day to have uninterrupted reading & reflection time before the kids wake up. It required changes to my night time routine, but I’ve found myself in a happier mood despite factors at work. Interestingly, it created a condition such that on most days, I do find myself being able to enter flow state.

There are some parallels between ikigai and flow: creating order in your consciousness, performing a specific task/activity, having a goal, and requiring some amount of focus, although the activity doesn’t necessary have to be autotelic or require psychic energy. In the context of this framework, I think the main differences are: (1) consistency and (2) sustainability. First off, it must be a routine, a condition one is in control of that’s replicated at a regular cadence, ideally daily since it should be the reason you wake up every day. Secondly, the activity must be sustainable. It's important that the task is clear, but the goal doesn’t need to be. In fact, there’s a danger in having goals clearly defined, unless you have a way to continually move the goalposts. Otherwise, once you achieve those goals, it becomes more difficult to recreate the blissful condition. To find sustainable happiness even in the mundane, you shouldn’t expect to increase your skill or the complexity of the task. With respect to team culture, it’s important for managers to respect and embrace someone’s obligations (like daycare drop-off) and rituals outside the office (like making time for their ikigai). Sometimes, those activities can be flow-inducing; at the very least, it helps people minimize distractions outside the office leading to better focus and flow-potential for experiences at work.

Flow-breaking

Below are work conditions which I’ve found to be detractors for my personal Flow state (not exhaustive, just some top of mind items).

- Changes in priority or leadership. When this happens, the team/org vision becomes fuzzy. The work being performed by members of the team, no matter intellectually challenging, may no longer align to the goal. Even if there’s no change in the goals, the disconnect or unknowns between deliverables and leadership expectation tend to cause churn, making it hard to enter flow state. It’s up to managers to get guide people back to their flow channel through better communication and building triggers into the operating model to adjust how the team should respond to these changes.

- Appropriate scope of work not available. Realistically, the appropriate scope with the right level of challenge isn’t always available. If the scope is too low or there’s a disconnect with the team goal, it can be challenging to find the right work to keep people stimulated. It may help to shift focus towards growing functional skills and leadership principles, and finding other career development opportunities.

- Challenges or risks too high. What I’ve found to be extremely flow-breaking is poor management of goals and team capacity. There are three interconnected constraints within any project: time, resources, and feature scope. If you assume resources on the team is fixed, then changing feature scope should require a reassessment of time. In cases when leaders set aggressive deadlines and take on new work without growing the team capacity, you end up high anxiety, overworked employees or unpolished features (or both).